At the start of 2016, The Guardian reported a ‘survey of workforce at 34 book publishers and eight review journals in [the] US reveals 79% of staff are white’. It isn’t a surprise that bookstores around the UK tend to reflect this lack of diversity, with few non-dominant narratives or books by people of colour, making their way onto our shelves. At the same time, a survey by London Short Story Festival, argues that ‘By 2051, one in five people in the UK, is predicted to be from an ethnic minority’.

Are things beginning to change with a greater focus on diversity in books? Recently I have witnessed an unprecedented amount of focus on mainstream publishers and literary agents in their attempts to reach out to BAME (a term generally used in the UK to represent Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) authors. Popular social media campaigns began with Naomi Frisby & Dan Lipscombe’s #DiverseDecember#ReadDiverse2016. Last week, we saw the introduction of major publisher Simon & Schuster announcing the imprint Salaam Reads for Muslim children’s books. We have also just witnessed the launch of the Bare Lit Festival, a much-needed global platform, hosted in London, for celebrating talent among BAME writers. One of the initiatives of Media Diversified (the organisers behind Bare Lit & other projects) is to increase the diversity within the publishing industry since, ‘BAME people are under-represented in the media industry by a magnitude of over 300%.’

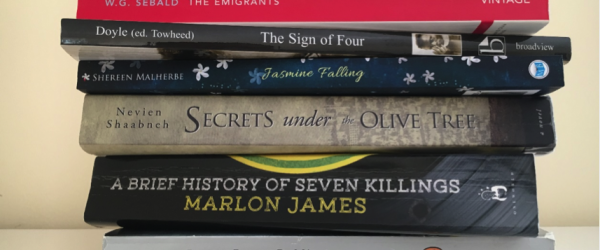

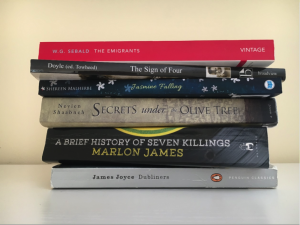

This all has personal resonance for me. I began writing my novel, Jasmine Falling a few years ago. My novel follows the journey of Jasmine; a British/Palestinian girl, who travels to Palestine in search of her missing father. I spent the last two years marketing it to the UK publishing industry. I have had a rollercoaster ride of anticipation, from rejections to full manuscript requests and promises of a contract. What became clear was an emerging pattern of responses mostly summarizing their inability to target or understand my market. A personal favourite of mine was when a response from a literary agent landed on my doormat explaining that ‘the Palestinian background [of my novel] jars with the chick-lit character.’ Did that mean my character was incapable of experiencing the same emotions as any other woman because of her heritage? I am not saying that is the sole reason my book wasn’t taken on by a UK agent or publisher. There are of course many factors that inhibit the entry of all writers, but surely the lack of diversity in the industry can’t help.

I was directed to go to ‘boutique’ publishers who ‘specialised’ in Islamic fiction, books with a relatable Muslim narrative. But I was uncomfortable about it being termed as Muslim fiction; yes, I wanted to reach out to a Muslim audience and to know that I had made a book with a relatable narrative, but what about everyone else? My book was penned with the intention that it could reach those who hadn’t explored Muslim/Palestinian narratives, so they could perhaps be introduced to them.

Pigeonholing books or authors into certain genres by author religion/culture could potentially exclude sections of the audience. It reminds me of the sidelines minority groups experience in society through stereotyping. I would like to be known as a storyteller first and foremost. I don’t want to exclude an audience who thinks the book ‘isn’t for them’, or be categorized primarily as a Muslimah author, considering that the religion of most other authors doesn’t precede their titles. Is this segregation happening with other forms of diverse literature too? Will diverse books be in their own section of the bookstore? This may have an effect of relegating them to only niche audiences and could exclude the point of the inclusion of diverse narratives in the first place.

Bloggers & book lovers such as Safia Moore and Emma Oulton, and book reviewers, such as Beth at Plastic Rosaries have started to reconsider how they purchase books and make more informed choices about what is on their shelves. By looking at the ethnicity, setting and sex of the authors they predominantly read, they are now actively seeking works by authors who they perhaps hadn’t considered reading before. I have had a few requests for my novel materialize from those seeking to understand more about the Middle East fiction and writers. Beth, for example, has diversified her book list according to the country in which the stories are set, and subsequently added mine to it.

It seems that the diverse reading initiatives are changing how readers buy, so perhaps this is the start of the change for a more representative UK publishing industry. I’d like to see the entry of more Muslim women characters and writers being taken on each year who portray the demographics rich narratives. There are success stories of Muslim women writers and characters published worldwide and to a Western audience. Examples include, Shelina Janmohamed’s, Love in a Headscarf, which has been translated into different languages worldwide. G Willow Wilson is the creator of the first Muslim Marvel comic book character and has had other titles published for a mainstream audience. Aisha Malik’s Sofia Khan is NOT Obliged has also recently hit the shelves. Each of these authors represent their own character’s narratives and those narratives differ from one book to another. Leila Aboulela (writer of Lyrics Alley, Minaret and other titles) said at the Bare Literature Festival, that she hoped a platform like this would ‘shatter the illusion that all diverse writers are the same.’ By including more diverse writers, with their own narratives and more visible platforms to host them on, the inclusion of writers of colour and other non-dominant narratives may begin to change what books we are currently finding on our shelves.

5 Comments

I guess it’s understandable that the publishing industry reflects the same ugly ignorant discriminatory practices as the species it lives off, Shereen. Did you know there’s a large (and growing) group of producers. readers and market within the publishing industry in the western world that has appropriated the ‘Christian’ label too? Without and endorsement or approval from the Christian community sector. I object to that trend on the basis that there is no publicly accountable supervising organisation representative of any particular section of the community to regulate or oversee individual writers or corporate producers (manufacturers) to ensure they subscribe to or uphold any recognisable or endorsed set of rules to ensure the product supplied to the market under the guise of the appropriated ‘Christian’ label actually meets certain standards the average consumer might interpret as ‘Christian’. Yet more and more corporate bodies are jumping on that money-making bandwagon. Who determines they are ‘Christian’ or that they abide by values or rules that might be considered ‘Christian’? Nobody, as far as I can see. Who says they’re more ‘Christian’ than their competitors? Again, nobody. The same faceless, unaccountable to the public or community group of businessmen are doing it to you, now, and an arbitrary list of your colleagues who, for all the anonymous group knows might actually have no religious affiliation but carry names like Ahmed or Muhammad. Fascism grew by similar stealthy means across Europe in the 1930s. It’s an ugly ignorant world at times. Maybe somebody needs to create a ‘Mammalian’ publishing sector to cover the ordinary non-extremist but curious majority of humanity.

Thank you for your message, Michael. You make some interesting points and I am sure there is a lot of cross over between ‘Christian’ fiction and the issues I mention above. Labelling it suitable for religious audiences also can be problematic as you pointed out, as everyone has different expectations and beliefs.

Shereen,

This was a very good post. It’s sad that publishers have so much control over what is made available to the public. I think it’s one of the reasons why more and more authors are going the self-publishing route. There are probably a lot of people who will be interested in reading your book, but the publishers are only looking for what they think will be the best sellers. I hope you get your book out there and it gets lots of readers.

Tina

Thank you for your message & support Tina. Self publishing has certainly opened up a platform for authors but unfortunately gets a bad rep due to the lack of editorial support which just isn’t available to a lot of self published authors and I’d like to see this change some how.

After a challenging (but absolutely worth it) experience, my novel Jasmine Falling is out now! For more information you can visit http://www.shereenmalherbe.com/Jasmine-falling

[…] To read more, visit Muslimah Media Watch […]