I have written extensively about media coverage of Latinx Muslims (here, here and here). My interest on the topic lays on my frustration regarding the amount of misunderstanding and erasure that goes on when people discuss Latinx Muslims. Most folks who address the issue do not understand Latinidad or the ways in which racial, class, gender and diaspora dynamics affect our experiences of conversion and how we place ourselves within Muslim communities. Also, I am very tired of people being overly worried about why Latinx folks convert to Islam. To be blunt, it is no one’s business.

Moreover, I am always incredibly annoyed at the ways in which coverage of Latinx Muslims can be so blatantly sexist and really so heavily invested on stereotypes of the “Muslim virgin” and the “Latinx whore” to explain how Latinx women experience Islam and decide to go from “wild girls” to “virginal Muslims” who abide to strict codes of modesty and segregated gender interactions. Besides, I cringe when I hear about Latinx Muslim dawah and worry about the ways in which dawah is conducted in Indigenous communities and the fact that often times missionary work is framed positively, when we know the epistemic and physical violence that comes with it in many cases.

Over the past ten years the narrative has not changed much. In fact, it has only been reinforced by centering the focus on Latinx Muslims in the US which, in a world of already complex identities, throws into the mix the dynamics of “empire” that bleed through artificial borders. To centre America-based Latinidad is to ignore that the majority of people who identify or are perceived as Latinx do not live in the US or even in the diaspora, and that their experiences may be radically different from Latinxs in the US.

Latinx identities are complex for a variety of reasons, including colonization, slavery and imperialism. Yet, the label “Latinx” has become synonymous with a shared experience that glosses over these issues. The term Latinx often alludes to people of primarily Hispanic linguistic background (can also include other Romance language speakers) with a “mixed” racial profile. That is because the myth of a united Latin America relies on the idea of mestizaje – the mix of Spanish with Indigenous and/or Black peoples. In places like Mexico, mestizaje has been official state policy, which has translated into state sanctioned violence towards Indigenous peoples, the erasure of Black communities and systemic exclusion against both Indigenous and Black folks. It is also worth noting that mestizaje as state policy is inherently patriarchal and goes hand in hand with sexual violence against Indigenous and Black women, third gender and non-binary folks, much of which gets reflected on stereotypical imagery of Latinx women.

Latinx identities are defined in relation to whiteness. This is not only “biological” (i.e. the “we are all mixed” narrative or “my great grandfather was Spanish”), but it is also cultural (i.e. “our cultures are a mix”). And while it is true to a degree that “mixing” happened in some areas and among some communities, much of it was under conditions of violence, genocide and slavery. The communal mingling between Black and Indigenous communities was also heavily policed and penalized in Latin America. Hence, Latinx identities have formed themselves upon the idea that they have a right to everything they touch… they claim closeness to whiteness when it suits them, and they engage in the appropriation of Indigenous and Black cultures and knowledges to distinguish themselves from other communities. Latinidad often excludes Blackness, which is why, for instance, Afro-Latinx like Amara la Negra have been heavily bullied by other Latinx. Latinidad also often recognizes the Indigenous past while ignoring Indigenous presents. For example, Latinx who claim “Aztec” heritage (eye roll… not even the proper term!), while participating in the oppression of Nahua people and other Indigenous communities.

To be Latinx is to be part of these complex systems of oppression, and yet (sometimes) struggling to find a space of belonging in diasporic contexts. This is not to say that you will not find Indigenous or Afro-Latinx folks as part of mainstream Latinx communities, because you will. But in diaspora settings other dynamics come into the mix. For Latinx in the US and Canada, the settler state tells us where we fall within the racial hierarchy, often treating us as a homogenous group in which neither Afro-Latinxs nor Indigenous folks fit nicely. We all end up being “Latinx”.

Adding Islam into the mix increases the complexity. While Latinx Muslims are one of the fastest growing communities in the US, there are also pockets of Latinx (white and mestizo), Indigenous and Afro-Latinx Muslims in countries like Chile, Mexico, Cuba, etc. Latinx folks, both in Latin America and in the diaspora, broadly engage in Islamophobia. It is not uncommon to see Hispanic media outlets associating Muslim imagery with terrorism, fundamentalism and conservativism. It is also not unheard off to see Latinx complaining about “Muslim immigration,” aligning with white supremacy movements that target Muslims or exercising physical violence against Muslims, particularly Muslim women. While some Latinx Muslims believe this is a matter of ignorance, I believe it has to do with how Latinx identities seek to align with whiteness and colonial narratives and how they access a level of power and privilege by doing so.

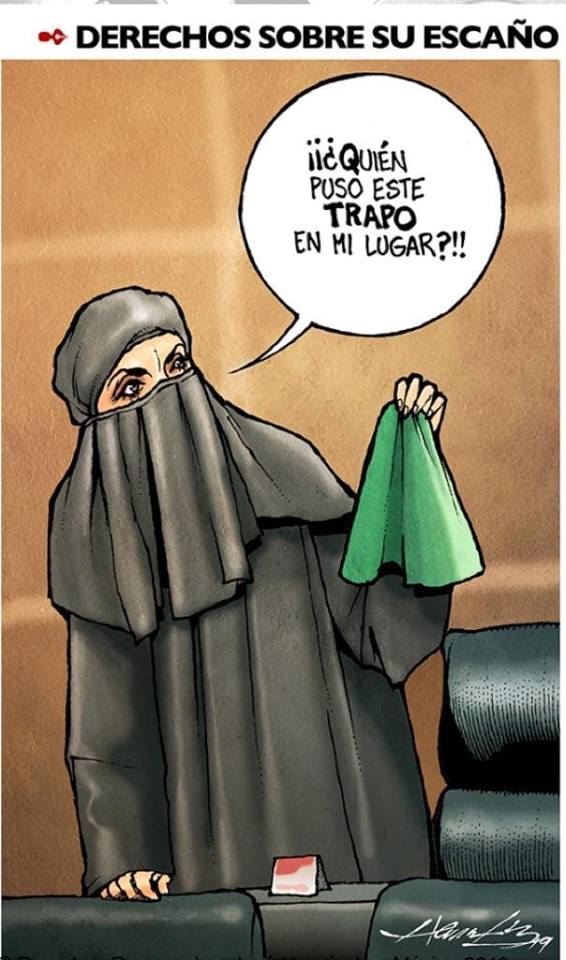

Mexican political cartoon by cartoonist José Hernández. It depicts northern Mexican senator Lilly Téllez , who has opposed decriminalizing abortion in Mexico. The green cloth has become a symbol of pro-choice movements in the country, and in the picture she says, “Who put this green cloth on my chair?!” Alluding to the use of the niqab in this image is a move often used by Latinx political cartoonists to mock political and social conservatism among Latinx women. The niqab represents oppression and “backwards” thinking.

Recently, VICE released a 19 minute Minority Report documentary about Latinx Muslims that provides an analysis of the flourishing of Latinx communities. Some of the reasons for conversion are speculated as due to the racism that Latinx and Muslim communities experience, as well as experiences with drug and gang related violence, mental health issues, among others. The report does not really pose anything new. Over the years, there have been numerous articles (here, here and here) dabbling into why Latinx folks are converting to Islam. Coverage on Latinx women is incredibly annoying on its focus on hijab, relationship to “male authority”, and the overall assumption of oppression. The video does not disappoint by showing very few women and only featuring moments of them talking about hijab and culture. The funniest part of the documentary is an interview with a white Latinx who is concerned about people converting to Islam because he believes Islam demonizes white culture… (*eye roll*).

While I have no interest in discussing people’s reasons for conversion, I find it very challenging to engage with the whole narrative surrounding Latinx identities and Islam. Latinx converts to Islam, to a degree, challenge their communities’ Islamophobia in a way, by adopting an additional religious/cultural identity. However, they also participate in existing stereotypical narratives about both Muslims and Latinx folks. For instance, they continue to perpetuate narratives that portray all Latinx converts as former Catholics (FYI Latinx aren’t all Catholic). They are also often found trying to convince others that there are no (or few) religious/cultural contradictions between Latinx identities and Islam, which isn’t always true. Also, they sometimes try to trace a link to Islam through Muslim influence in Spain, without critically thinking about processes of colonization and imperialism.

Further, Latinx Muslim women often center hijab and modesty as a core element of their conversion to Islam in an attempt to distance themselves from sexualized stereotypes surrounding Latinx women. This sometimes results in Latinx Muslims slut-shaming other groups, particularly Afro-Latinx women, and engaging in homophobia and transphobia. And, overall, Latinx Muslims continue to speak of Latinidad as a “bridge between cultures” – meaning between Latinx people and Muslims. In talking about a “bridge between cultures” Latinx folks, knowingly or not, align with the ideas of mestizaje, which homogenize experiences and erase the ways in which Latinxs exercise and participate in colonial violence. And while I understand the urge to claim such homogeneity and unity, particularly in a time where the political context has done a lot to target Latinxs, Muslims, Black folks and other communities, it is important to recognize our own role in the oppressions of different communities.

Latinx Muslims cannot be a bridge because, as communities, we uncritically participate in systems that are inherently exclusive, appropriative, oppressive and violent. The problem is that Muslim identities are sometimes used in Muslim Latinx settings to gloss over distinct histories of oppression in settler contexts, leaving Indigenous and Black folks at odds and the violence untouched. Being Muslim does not erase colonization and slavery, and it does not erase anti-Indigenous racism and anti-Blackness among Latinx communities. Being Muslim does not automatically create a united community with shared values, either. Until Latinx Muslims can deconstruct their own role in perpetuating systems of oppression while reconciling their experiences within the settler state, they will continue to bring along racist, classist and patriarchal attitudes into their Muslim communities.