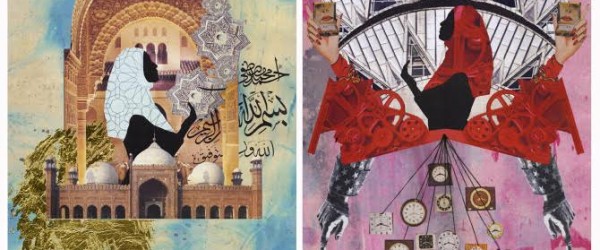

All too often, art relating to Muslim women blurs the lines between challenging and mimicking stereotypes. Other times, Islamic art is reduced to “calligraphy and rugs.” There are, of course, spaces that cultivate and present a diverse selection of Muslim art, but these spaces are too few. Western narratives tend to prefer to portray Muslim women as victims who stem from a homogenous culture, and tend to focus more on how they look then what they’re doing.

Azzah Sultan, a senior studying Fine Arts at Parson’s New School of Design in New York seeks to force her audience to rethink their perceptions of Islam and Muslim women. My interview with her is reproduced below, edited for concision and clarity.

Sarabi Eventide, Muslimah Media Watch: When did you come to start depicting Muslim women in your art?

Azzah Sultan: Before going into art school I was more of a “let me paint a picture that looks pretty and see what else I can paint that looks pretty” kind of artist. It was only during the start of junior year that I started painting Muslim women, specifically Muslim women who wore a headscarves. Interestingly, only when I started painting Muslim women did people started to question the subject matter that was being painted. Before I would just paint white people in general, a person of “white descent” you could say. I started doing that around sophomore year you could say, and after that I was basically, “Ok! I’m going to do this from now on. I’m going to try and challenge certain stereotypes and just try and create a dialogue.” I really don’t like saying “dialogue” because it’s a bit of a cliché.

Eventide: Is there anything in particular that caused you to move toward Muslim women, or was it a natural progression?

Sultan: I feel like it was a natural progress for me to focus on Muslim women, because in a way it’s me exploring my own identity. Right now I’m at a stage where I want to focus on the concept of being Muslim in America and using art as a platform for Muslim voices to be heard.

Eventide: Can you start by telling me about some of your early work?

Sultan: I started this whole process of talking about Muslim youth, specifically, and Muslim women within a Western context through painting. That was the first medium I started to explore where I would paint Muslim women in different situations. For example, I started painting an image of a woman in a hijab in the style of famous pop artists such as Roy Lichtentstein, Andy Warhol, and Jasper Johns. It’s kind of a pun, a bit of a satirical look at whether she is considered a modern Muslim woman, now that she is painted in this style of what can be considered modern art. It’s dissecting the stereotype that a lot of Muslim women are “backward thinking” or “traditional” and even if in your opinion they are backward thinking, who are you to criticize that?

Afterwards I did a few more paintings that were a bit more confrontational, where the woman in the hijab looks specifically towards the audience. In doing so I’m breaking this expectation of her shying away, of her having to be quiet when in fact many of us are very outspoken and not naïve at all.

Eventide: What were people’s initial reactions?

Sultan: First they were afraid to talk back, or perhaps they didn’t want to come across as offensive. My painting a person of color, specifically a Muslim woman of color really helped people open the door; my painting helped them look at a depiction of a Muslim and try to analyze it. I started a conversation about race politics and religion, and about how Islam is specifically viewed within the Western society.

Eventide: Why and how did you move from using paint to using other materials?

Sultan: I’m working on story telling and I’m very interested in using different materials to create a safe space for Muslims and giving a platform for other Muslim voices to be heard.

I became more interested in what are the mediums I could use to have a more interesting conversation about the displacement of Muslims within a western society. I started taking selfies of just myself and a policeman, or a police person, behind me. I titled it “Photobombing.” The actual definition of photobomb is when someone is behind a picture or disrupts what is being taken. It’s a very dark subject matter to be honest, but I’m playing on this idea of a bomb and kind of reversing the role of the stereotype that Muslims are terrorists. From then on I started thinking, “What art can I make that does not seem very clichéd, that does not seem very one-dimensional?” I feel like for such an important subject matter you have to have use of material, because you don’t want it to be a slow conversation. You don’t want it to be super literal because you want people to analyze the work and really think about what they really believe about Islam and challenge those stereotypes about what they think about Islam. I moved away from photography and painting.

I started using fibers, materials, and fabrics. Embroidery and stitching in a way are something that is somewhat permanent but at the same time something you can completely take apart. It’s this idea of leaving a mark behind that interested me, so I started embroidering a lot of patterns that Muslim women gave me from their specific culture into these loops. I took portraits of the women and having all of these embroidered patterns around them is challenging the misconceptions of how culture and religion play together. A lot of the views people have of Muslim women being oppressed it stem mainly from cultural practices. the stem from from how they were raised as opposed to what Islam actually teaches us.

From then on, I started stitching an American flag of these scarves that different women across the states sent to me. I really like collaborating with Muslim other people when making my work because I don’t think it’s really right to give my own opinions of Islam. There are so many followers of the religion and my voice shouldn’t generalize an entire faith. By collaborating and having a lot of Muslim women and Muslim people as subject matters and working with me, then I am giving a platform for other Muslim women to speak about their faith. What really strikes me right now is how I can create a platform for other Muslim people to speak because, I don’t know if you really see this, but a lot of the times whenever art is made about Islam, it’s sort of a negative light. Especially conceptual art, where it’s just like “oh yea, let’s focus on how Muslim women are oppressed; let me just show you this.” Instead of that, I want to focus on having art as a way to talk about Islam. In a way it’s sort of like, I don’t want to say it’s sort of like dawah (the preaching or teaching of Islam), but it’s my way of discovering my own faith at the same time. I integrated social practice into my art practice– ha, I hate saying the word “practice”– by researching my faith. That way I have to be sure that whatever I’m representing about Islam is the actual true ideology of Islam.

Eventide: I’m interested in your “Newsfeed” piece, can you tell me about that?

Sultan: I began to realize how text can illustrate certain stories, and the word that’s been stuck with me recently “displacement.” I find it interesting that the Prophet Muhammad (sallalahu alaiyhi wa salaam) and his companions were persecuted in Mecca and felt a sense of displacement. I feel like in a way that sense of displacement is very apparent here in America with a lot of Muslims and Muslim youth who feel their faith is not welcome. There’s a constant reminder of what the media outlet portrays as their faith. For a month I collected all of the articles people would post on Facebook concerning the backlash Muslims are facing in this country, in terms of what Donald Trump is saying what all these politicians are saying about faith and I printed them on the material that newspapers are printed on. The piece speaks to to what us millennials are facing. Most of the news we read is online and printing it with this material emphasizes how much information is accumulated from the media. I created a scroll out of newsprint and started layering it over and over again to the point where you have to roll it to fit it into the space. You can see the sheer amount of material there is out there and how upsetting it is that you constantly have to see this news about your own faith.

Eventide: What piece would you consider the most controversial?

Sultan: I think my most controversial piece is the American flag that I created out of headscarves. I had different women from across the states mail me a scarf either in the color blue, red or white. I then hand stitch these together to create a flag. I was inspired by David Hammons’ “African American Flag” piece. In a way this was a way for me to prove that these women are still American even though they were Muslim, at the same time i poking at the idea of American patriotism and how sometimes it can be really intense in the country. The piece is called “Home Sweet Home.”

Eventide: What is it like being a Muslim woman in the art institution?

At times, people may want you to be overly outside of your own comfort zone. That’s probably the same with all artists– people just want to push you– but when there are certain limits that you can’t push because it might compromise your faith, it’s a bit hard for people to understand that. I think a lot of artists of color are in a similar situation. They’re afraid to become a trope; they’re afraid to become a cliché. People will constantly want them to fit into a different stereotype of what a person of color artist should be, and they want Muslims to be a radical. They want you to be super rebellious in your art. They want you to do all these performance pieces, but I’m not comfortable doing that. At the same time I don’t want to be “safe” with my work. I want my people to allow people, at first, to come and ask, “what is this work about,” then it hits them. My art tells you what the piece is about and you start to question yourself and question what people think about what Islam.

Eventide: It’s unfortunate that people cannot always accept the boundaries of your belief. What other criticisms do you have of the “art institution”?

Sultan: It’s very Eurocentric as well. You have to cater to a certain Eurocentric audience sometimes, and I’d rather cater to other Muslims. I feel it’s also important to cater western society because they’re the ones who need to know more about Islam because of the different perceptions they might have. I don’t want to be a sellout.

Eventide: What do you aim to achieve with your art?

Sultan: I guess that the main basis of what I want to create and the reason I want to create art is to create something that gets people talking about these issues, even though they feel like they might say something offensive. At least they are saying something and being educated by it.

I’m still young, I’m still learning. I don’t have a fully-formed idea of what the art world is yet. I’m still trying to grasp as much knowledge and information as I can get, so even though I sometimes feel like my faith is being compromised or I feel like I have to become an artist I don’t want to be, it is good for me to push myself, to challenge the pressure I feel because that itself will create stronger art. I believe it will leave a bigger impression on people and make them really think about what is it like to be Muslim here in the United States. Why is it so difficult for us to be who we are?

Azzah does not currently have any open exhibitions, but her art can be found on her website.