Upon learning about the Paris attacks and the #PrayforParis hashtag that emerged, I felt many things – but I was not shocked. Violence does not shock me. As a woman of colour and as an immigrant, it is part of my surroundings.

I have become desensitized to violence. If you are like me and grew up in a Third World country that has experienced violence during your lifetime, chances are you understand.

Growing up in Latin America in the 90’s in 2000’s I witnessed hundreds of missing and murdered women in northern Mexico, the rising of the Zapatist Army and the violence targeting Indigenous communities by the Mexican government, the Acteal Massacre, theGuatemalan genocide, the violence in Colombia, the numerous terrorist attacks in Peru and the following brutality of the Fujimori regime, and many other so-called “low intensity conflicts,” including police brutality against black communities in Brazil. I also vividly remember the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan and the multiple attacks against Palestine. All of these have had visible and horrible effects on women, particularly because rape and torture as weapons of war have been common.

Since moving to Canada, I have personally experienced racism, stereotyping and Islamophobia after my conversion to Islam. What is more, I have gotten to interact with women who have been particularly marginalized in a country built on settler colonialism. I have heard the voices of the families of missing and murdered aboriginal women. I have heard the stories of immigrant women of colour who face barriers to accessing services, experience racism and are simply not welcome in the country. And I have seen Islamophobia not only in the streets but at the highest levels of government and the political sphere.

So, I am desensitized. Violence does not surprise me. I have come to accept that it is part of life, my life as an immigrant woman of colour and as a Muslim.

In the wake of the Paris attacks, I learned about the attackers and those they killed, and I learned Syria would continue to be bombed, now by France.

But I couldn’t separate that violence from what is too often dismissed as the violence suffered by the inhabitants of the “third world”, and those marginalized in the West. These are just some of the experiences of violence that have been important and relevant to me:

- Mexico has 43 missing students and 15 currently arrested at the hands of the Mexican government. There are also thousands of missing and murdered womenas a result of the rampant violence and more than 150,000 innocent killed in the so-called War on Drugs.

- Canada has thousands of missing and murdered aboriginal women, dozens of targeted Muslim women (some examples here, here and here) and a mosque was just set on fire in Peterborough, Ontario.

- The U.S. has also a rampant issue of violence against Indigenous women andtransgender Latina women, not to mention high levels of Islamophobia that have tangible effects in the lives of Muslim women.

- We all followed #bringbackourgirls only to later forget about the women and girls affected and remain silent on 2000 lives lost to Boko Haram.

- Kenya lost 147 students last April to an Al-Shabaab attack and dozens more since then.

- Lebanon lost 40 civilians in the last ISIL attack not to mention the spill-over effects of the Syrian conflict and the refugee crisis.

- A suicide bomber recently killed 19 people at a funeral, but for the past few yearsIraq has born the burden of extremist violence in addition to an occupation that left more than 1 million dead.

And this list does not even begin to cover the rampant violence that the Third World and people of colour experience on a daily basis.

***

All of this however, does not mean that I cannot empathize. I felt deeply concerned about my fellow writers and friends who have family and friends in Paris. Fear and worry are something we experienced together as we also silently prepared for the wave of Islamophobia, across the Western world, that we know will follow.

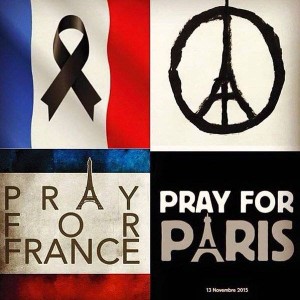

We were not the only ones thinking about Paris. Many Muslims reacted by engaging with the #IamAMuslim hashtag and condemned ISIL. Canadian Fariha Naqvi-Mohamed explained why ISIL does not represent Muslims, while Hasnaa Mokhtar described why she will “#PrayforParis but won’t apologize.” However, I kept feeling uncomfortable.

Why wasn’t the media talking about Lebanon or Iraq?

Not only did Facebook create a Paris profile flag and a safety feature for those in Paris(a critique is available here), actively neglecting the situations in Lebanon and Iraq, but Twitter was flooded with messages about Paris and prayers for Paris and solidarity for Paris. Even among Muslims much of the reactions focused on the attacks against the western country.

Why?

Chris Graham writes about the “selective outrage” that followed the attacks against these three countries, making a case to why people should identify with all the victims of terrorist attacks. Something that he mentions in passing is, however, essential to the reactions around the world. The white-Western standard prevails.

Even as Muslims, and often as people of colour, we feel we owe the West an explanation whether it is in the form of solidarity, apologies, prayers, etc. I see angry messages from Muslims and people of colour floating around about why we should care about Lebanon and Iraq, but I have yet to see a collective effort from Western Muslims to apologize or express solidarity to the victims and survivors of the attacks in Beirut and Baghdad.

Unfortunately, this is not a rare attitude and it goes beyond Muslim communities. Mexican activists involved in the search and advocacy for the 43 missing students, which I have been personally involved with, were outraged with the #PrayersforParis hashtag after fighting for over a year for a few drops of media attention and Western solidarity. The hashtag was a reminder, to many of us activists of faith and colour, that our lives are dispensable against the Western standard.

Of course it is right that people express concern and support for France, after all innocent lives were lost and many more will be attacked because of this display of terrorism. Muslims will likely be the first to feel the wrath of the West retaliating in France and across Europe. But we also need to wonder why is it that we, even as people of colour and of faith, continue to prioritize and neglect the struggles of people in the Third world, of Indigenous peoples, of Muslims in non-Western countries and of black peoples everywhere? Why is it that we still rush to explain to the French that this is “not real Islam” or that this is “not our Islam” while leaving everyone else behind?

In the Canadian case, I particularly worry about my fellow Muslim sisters because Muslim women in Canada have consistently faced sexism, racism and Islamophobia. We have seen the attacks against Muslim women across provinces and the targeting of our mosques. However, I think it is important to remind ourselves that these oppressions are part of a broader system that affects other women as well, but in different ways. We cannot continue to consider non-white lives dispensable and we should not continue to normalize violence against people of colour because that is a feature of white supremacy… the same white supremacy that has led many of us to apologize and explain our Islam to France while neglecting to talk the violence affecting the lives of people in the Third World and people of colour in the West.