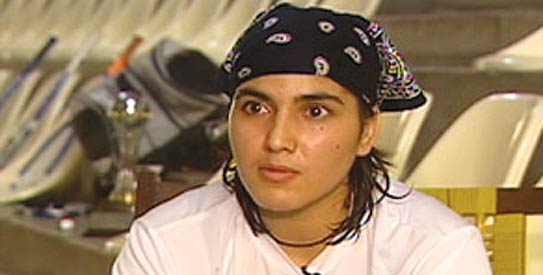

In a 2010 television interview, quoted in a more recent article (I was not able to find an original recording of the interview), Pakistan’s highest-ranking female squash player, Maria Toor Pakay, spoke on the rights of women in Pakistan:

“Girls don’t get any rights. They cannot go out of the house. They cannot do whatever they want to do. They get married when they are 12, 14; they are not allowed to get an education. They are not allowed to play sports. They have to stay covered; if they don’t, they are killed. All the time I wish that I could make a change.”

I assume that Pakay’s comments were especially representative of her home in South Waziristan (specifically Bannu, where she was born). Media coverage of Pakay’s achievements is heavily focused on her roots in this region, making particular reference to it being the “home of the Taliban,” where “terrorism is a way of life.” Even local news media underscore her connection to this conservative tribal region of Pakistan.

As much as I admire Maria Toor Pakay’s strength and resolve in her journey to represent Pakistan among the world’s top-20 women squash players, I find her statement above to be partly misleading when applied to Pakistani women and girls as a whole. Such sweeping comments actually take away from those women who have found success in their respective fields in Pakistan’s male-dominated society.

Less attention is often given to sportswomen like Sana Mir, Shabana Akhtar and Kiran Khan, who have found success in cricket, athletics and swimming respectively. Perhaps it is because these women have not escaped the oppressive influence of the Taliban in South Waziristan? While this in no way downplays the successes of women of that region, it is equally important to commend the successes of all Pakistani women who have worked hard within an oppressive, patriarchal system to achieve recognition within their respective fields. While Pakistani women participating in sports at a professional level is still largely a new phenomenon, there are many women who are actively participating with their male counterparts in various fields in the public arena. In a recent MSN news photo gallery, ten powerful Pakistani women were identified, ranging from politicians, writers and entertainers. This collection identified women like Hina Rabbani (Pak Foreign Minister), Academy Award winner Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy (documentary filmmaker) and Asma Jahangir (human rights lawyer) as women who were defying stereotypes and exemplifying the potential of Pakistani women across the country. Therefore, by equating South Waziristan with Pakistan in so much of the coverage about Pakay, the stories of courage and determination displayed by the aforementioned women is sadly ignored and only serves to perpetuate stereotypes of all Pakistani women as repressed and uneducated.

Historically, it is not untrue to suggest that sports and women have been considered a volatile mix. Women in Pakistan who have participated in public soccer games, running marathons and squash have been met with backlash from conservative factions, who claim it is immodest and therefore unIslamic. Recent trends, however, suggest that more and more Muslim women are taking up professional sports further buoyed by an industry promoting modest and flattering clothing for Muslim sportswomen.

Legislation on the rights of women in Pakistan finds its source in understandings of the Quran and Sunnah, which are encoded in the country’s personal status code. Pakistan over the years has introduced numerous legislations to protect the rights of women. This include laws regarding child marriage, divorce, polygamy, women’s representation in parliament, and even protection of women against workplace harassment. When public institutions are unable to implement such policies, it becomes a problem of governance, making lack of policy implementation a key obstacle towards achieving equal rights for women in Pakistan. Additionally, the varying interpretation of Shariah further underscores socio-economic divisions. For instance, we cannot expect a highly educated, gainfully employed, middle-class woman from key urban cities with the freedom to choose her spouse and who expects to inherit based on her religious denomination, to have the same level of intense feeling of deprivation as a poor, rural Pakistani woman. I agree with Pakay, that religious doctrines related to women are part of the problem. They should be subject to interpretation (ijtihad) based on present day context, under the delicate supervision of a council of highly educated scholars.

All of this aside, Pakay, 21, is Pakistan’s No. 1 ranked women’s squash player and as of May 2012, she is ranked 67 in the world. She moved to Peshawar, and with the support of her father (and her own initiative and hard work), was eventually able to secure top coaching and sponsorship in squash. Her story of success is important and a source of pride for other young women (irrespective of their ethnic background) to pursue a career in professional sports. Let’s use her story to inspire all Muslim women, whether in Pakistan or abroad, because any inroads she makes in the world of squash will only guide us to strive further to achieve our potential.