Earlier this year, South African Muslim media was abuzz with the story of Dr. Aafia Siddiqui, an American-educated Pakistani cognitive neuroscientist who was convicted and sentenced to 86 years in prison for assault with intent to murder her U.S. interrogators in Afghanistan. The media campaign served to raise awareness about Siddiqui’s alleged abuse at the hands of the U.S justice system, and to assert her complete innocence. Her story is a difficult one, spanning the vastness of two continents and the complexity of terrorism politics in both of these. This post is not meant to cover the Siddiqui case, or to make any judgement claims as to her innocence or guilt. I would like to add that I sincerely advocate for justice for Siddiqui, who has no doubt suffered tremendously – whatever her political inclinations.

The focus of this post is the treatment of Siddiqui’s case in recent South African Muslim media. I am often accused in my community of unduly and unnecessarily vilifying the Muslim media, so I must add a disclaimer – that pointing out discrepancies in the media’s treatment of Muslim women or issues pertaining to gender is not an attack on all the work of an organization, but meant to create dialogue on how Muslim women can be better represented. The groups I speak of articulate a certain kind of gendered ideology, and it is their right to propagate this discourse. I do, however feel that, living in the multicultural and vibrant democracy of South Africa, alternate expressions of Islam and Muslim women need to be put forth.

Back to the case at hand: what was peculiar to me about the whole thing was the way it was handled. It brought to the fore deeply entrenched notions of “honour” which (some) Muslim men hold. Channel Islam International initiated the “Free Aafia Siddiqui” campaign, which included a national speaking tour by Siddiqui’s sister Dr Fawzia Siddiqui and human rights activist, Altaf Shakoor. The campaign was then picked up by other media outlets, like Radio Islam, Voice of the Cape, and Muslim Views.

I found it quite promising and appropriate that it was Siddiqui’s sister, herself a highly educated and articulate woman, who was primarily representing this story. Not only was she the main voice on all interviews given throughout the country (including SAfm, a national radio station), she was also given the platform at various events aimed at fundraising and creating awareness for the Free Aafia campaign.

What I did find strange was the double standard of this, coming from establishments (CII and Radio Islam) that do not encourage higher education and public-speaking personas for women. Muftis (scholars who issue religious edicts) unequivocally state on these radio stations, during Q&A sessions with the public, that women are not permitted to attend universities (they may, however, study through correspondence/distance learning), work outside the home (except in cases of dire necessity) or assume positions of leadership (outside the home). Discussions around women focus around their role in the home, as mothers and wives. Women’s political participation is seldom discussed, except for making du’a and contributing monetarily to the Palestinian/Iraq/Afghani (insert other oppressed Muslim) cause. Strange then that Siddiqui’s case would be taken up with such gusto, as she was not known for staying quietly at home but for her high level Western education, career and activism, and her case (whether true or false) is replete with political involvement, particularly with Islamist tendencies. That Siddiqui’s sister would be welcomed with such enthusiasm is strange as well – women travelling on their own or with unrelated men are not looked favourably upon, and according to these organizations’ protocols, it is also impermissible for women to address mixed gender settings, as was the case with all the speaking events held to raise awareness for the campaign. I highlight these discrepancies to point out that all the usual rules and restrictions seem to fall to the wayside when it comes to issues that the media (who represent religious authority in this case) deem important – i.e. poor Muslim woman held captive by Americans.

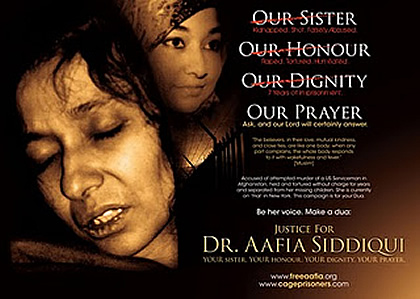

So why the duplicity? This brings me to the crux of the issue – the use of Aafia Siddiqui as a poster woman. As a Muslim woman incarcerated by the “West,” she falls into a larger pattern of anti-Western sentiment, the perceived (and certainly in many cases actual) dishonouring of the Islamic sacred (where women and their “honour” are central). Stories about “sister” Aafia are replete with descriptions of how her honour has been compromised (apparently, there is nothing worse than a Muslim women being controlled by non-Muslims), and that Muslim men should assume their rightful positions as leaders, to save her from this disgrace. She is also referred to as an “imprisoned rose”. That she is a victim of abuse, not by her family or religion, but at the hands of Americans, generates sympathy amongst listeners and, of course, ups ratings. Her persona is painted in an overtly religious way, from her Islamic studies training and memorization of the Quran to involvement in religious affairs like the MSA. The impression given is that Siddiqui’s case represents an assault on Islam as a whole – a common motif when it comes to the treatment of Muslim women.

Many of the articles were sprinkled with pictures of Siddiqui in her pre-prison bare-headed youthfulness, followed by a scarf-clad, tortured version of her. This opens up a host of concerns for how the female body is implicated and symbolically deployed in discourses of power to justify ideology – in the words of a friend, “pro-Taliban effort concealed as concern for Aafia.” The campaign implicitly accepts her innocence (which I am not disclaiming), without questioning the broader issues of extremism and terrorism to which the case is linked.

I am not implying that South African Muslims should not seek justice for Siddiqui, but that we should be aware of the discrepancies in the relaying of information pertaining to her case as well the usage of her image and her body to symbolize a preoccupation with the “honour” of Muslim women.