I was hit by a case of déjà vu when reading two recent articles discussing the work of Makan Emadi, which MMW has discussed before. In a piece posted at the Daily Beast, Betwa Sharma boldly claims that Makan’s work is part of a rise in “Islamic Erotica.” Sharma says that Muslim artists are depicting Muslim women as pin-ups. The mainly discusses an ongoing debate about Islamic rulings on the depiction of human beings.

Rather than being indicative of a rise in the fetishization of Muslim women, the term “Islamic Erotica” seems to be a sensationalized label for a debate no different than the other intersections between culture and religion. It feels as though the discussion of nude bodies in veil-swathed Muslim communities is automatically a form of erotic work. Furthermore, it’s like a pathetic attempt to inspire controversy.

What is most frustrating is that, while artists may come from Muslim backgrounds, they should not only be engaged on the basis of their religious identities. The way in which certain rulings play out into one’s life are only indicative of their own lives, rather than a global trend or problem. Thus, I do not connect Emadi’s work with a “rise” in “Islamic Erotica,” nor do I see the existence of Muslim artists creating work that involve themes of nudity as indicative of such.

Both The Daily Beast and a piece from Houston Belief applaud Emadi’s work as controversial and perhaps even as a sign of progress. This is disappointing for several reasons. First, his is work is hardly indicative of the discussion of art within the Islamic community. More importantly, he simply portrays all Muslim cultures through one lens, not because that is the way that the media may depict women, but because of his own personal feelings about the treatment of Muslim women in Iran.

I applaud Emadi for combining the images from both his Iranian and American selves in order to inspire conversations about the objectification of women. At times, it is easy to forget that the hijab can too objectify women. However, Emadi defines it as more of a broad oppression against women, hardly acknowledging the diversity that plays into the relationship between the hijab and the women that wear it.

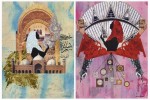

In the article on Houston Belief, Menachem Wecker also discusses an intersection between faith and art, even though Emadi’s work is not an extension of the debate about the depiction of nudity within Islam. Wecker profiles Emadi’s newest series, “Modesty,” which showcases pictures of celebrities covered up in niqabs (pictured above left is Britney Spears in a niqab from the “Modesty” series).

In resurrecting such problematic images, this type of art reinforces ideas about Muslim women needing “Western” mediums in order to find liberation, not only for their bodies, but even within their professional lives, specifically as artists. I wonder why the depiction of nude bodies is only of value when pertaining to the naked bodies of women. Once again, women are represented as objects to be looked at, assuming what their lives are like. Thus, while the idea that “Islamic Erotica” is on the rise is questionable, the artwork itself unquestionably only serves to further silence and stereotype Muslim women.

Furthermore, the depiction of life forms is not simply about hijab, or covering up women–it touches animals and men. I feel like the depiction of animals is not as sensational, hence a lack of coverage about the debate on illustrating these images. But why no images of Bin Laden with a turban and six-pack abs?

The objectification of women does not really help anyone ponder gender stereotypes—if anything, it only contributes to depicting Muslim women as creatures that are seen, but not heard. Let’s stop pretending that sexualizing women is groundbreaking or artistic and just call it what it is: sexist.