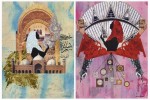

The Saatchi Gallery’s latest exhibition Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East has received considerable media attention. Despite the overused term, the art is refreshingly original, featuring 19 artists, most of them in their twenties and thirties, from Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Tunisia, Lebanon, Syria and Algeria.

Their art is raw, tender, vicious and vile. Think the Middle East is messed up? Their art is unapologetic, featuring images of homosexual naked Muslim men and Iranian prostitutes and transsexuals. “Ghost” (front view pictured left) by French- Algerian artist Kader Attia is hauntingly reminiscent of the images of women so often shown in war-torn and ravaged, destitute places that seem to comprise the Middle East now. I disagree with Adrien Serle at The Guardian, who thinks Attia’s representation of 200 kneeling veiled women is unimaginative.

At first glance, it does concede to the stereotype of the dark and lifeless Muslim woman; however, my first thought was how strikingly similar the women are to the hooded men of Abu Ghraib. In his own words, Attia says his art work is more about the experience than an object: “The shape is only necessary as a reference to its history.”

At first-glace perhaps, “Ghost” is too straight-forward (Serle calls it “weak, boring, stuff”), but is that so bad? Have we become so accustomed to the hidden nature of the intellectual, so cynical of the simple, so predisposed, if not unwaveringly susceptible to ulterior motives that we only accept art that is multidimensional? I say, in a world filled with conspiracy theories, why not take a moment to appreciate the palpable? Serle’s piece, like the history of western attitudes toward the Middle East, does not recognize that even after wars, innumerable death and hair-pulling complexity, genuine simplicity will always be found in the Middle East.

At the Times Online, Joanna Pitman had a more favorable review, calling Ghost “one of the most arresting” works in the exhibition. On approaching the women from behind she says,

“You expect to hear the murmur, the gentle susurration of prayer, but as you turn at the end of the room you see that these women are hollow figures, vacant shells of tin foil, each with a gaping black hole where the face should be swathed in the veil. Attia’s image of emptiness is heavily political, the shrouded, veiled, yet empty, figure of Muslim women presented as the symbol of divergent struggles over decolonisation, nationalism, revolution, Westernisation and anti-Westernisation.”

It’s interesting that Pitman recognizes their individuality, even though they are presented as uniform. It proves that it is possible to see your friend and your enemy through the same lens, both rooted in individual strength, against collective, perpetual victimization.

Note: The Times also has a slideshow of some of the other artworks on the sidebar here.

UPDATE:

Editor’s Note: Muslimah Media Watch regrets any offense caused by some of the wording in this article, which has been discussed in the comments. The wording will not be removed in the interests of transparency, but we sincerely apologize for our failure to uphold MMW’s aim of inclusivity.