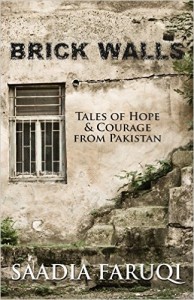

Brick Walls by Saadia Faruqi is a collection of seven short stories set in Pakistan, featuring a diverse cast of characters, from Asma, a widow struggling to feed her child, to the priveleged Rabia, who finds that wealth does not always protect women, to the precocious ten year old Nida, an aspiring cricketer who is not put off by being told that “only boys can play cricket.”

Subtitled Tales of Hope and Courage from Pakistan, the stories reminded me of the traditional genre of stories which follow the maxim “ina ba’d al-‘usri yusra” (after hardship there is ease).This is not to say that the stories in Brick Walls all end happily and hopefully (they do not), but that the conflict in each story has to do with the determination of the protagonist to claim their lives and not let difficult circumstances defeat them. In some cases, the hardships are over quickly, in others however there is no guarantee that they will ever be over. Consequently, the tone of the stories range from light and humorous, as in Nida’s story, to a darker investigation into the nexus between marginalisation, terrorism, and religion in “Paradise Reinvented,” or how corruption feeds injustice as experienced by a falsely accused woman in “Free My Soul.”

Faruqi is able to take on the voices of each of her diverse cast of characters, voicing ten year old Nida as convincingly as that of the elderly, crotchety but warm hearted Farzana. My personal favourite of the protagonists, Farzana lives alone after her husband’s death and after both of her children have decided to immigrate to America. The story revolves around her son’s attempt to convince her that she should not continue living alone in her homeland and her resistance to this idea:

“Now that Abba has died, why don’t you move here with me? I really worry about you being there in Pakistan all by yourself. It’s no place for an old lady, you know that.” Farzana was suddenly incensed. Who was he calling an old lady? She wondered why he was offering this proposition today, just a week after he had announced the happy news that he and his wife Jessica were expecting their first baby. “No!” she said more forcefully than she had intended. “This is my home, I’m not moving away from here. And especially not to a country like America!”

Farzana’s story reminded me somewhat of “Winterscape,” by Anita Desai, about an American woman who meets her Indian husband Rakesh’s mother and aunt. Although there is an element of the melodramatic about the violent incident that causes Fairuza’s change of mind, the writing is compelling enough to carry the reader along.

The melodramatic appears again in Faisal’s story, which deals with a young man’s encounter with an extremist group. Perhaps because of the difficulty of covering a longer time span in the form of a short story, Faruqi takes some shortcuts here which might stretch credulity. Again however, the writing bravely tackles difficult issues with nuance, showing the contrast between Faisal’s mother’s religiosity and the extremists cynical use of religion, and exploring the complexity of motivation, the “spectrum of desperation, self-pity and self-hate” that Faisal encounters in the group’s members.

The collection is largely focused in women, and the struggles women face, from a controlling older brother to a widow struggling to find someone to care for her sick child while she works, to an employer’s revenge when a servant rejects his advances, to everyday street harassment. This last is presented somewhat problematically, as the character subjected to “men’s looks” describes it as a compliment. The intention may have been to critique this view as a form of internalised misogyny, but if so it could have been confronted more deliberately.

While most of the stories are focused on female protagonists, the two stories with male protagonists work well as a pair. As mentioned, Faisal’s story features an aimless unemployed man drawn into extremism, while the protagonist of the other story is a Pashto rock singer fighting against it. The fact that one of the stories has a rock singer as a protagonist might tell you something about the fresh perspective these stories bring to sadly pervasive stereotypical ideas about Pakistan.

Too often today Pakistan is defined by the news. As Faruqi writes in her foreword, “most westerners think of it either as a haven for extremists or a prison for women and minorities.” It is the place where Bin Laden was found. it is the place where the “real Taliban” is hiding, it is the country featured in the TV show Homeland as sinister and terrifying, where children are used as bombs and everyone is lying.

Brick Walls does not shy away from the many problems Pakistan faces today – as Faruqi points out in her foreword, “the poverty is deplorable, the politicians are corrupt, and religious strife is troubling.” However, these seven stories insist that there is more to this nation than what we see in the news, contributing to a more complex understanding of this large and diverse country.