A few months ago, I wrote about the “rediscovery” of Noor Inayat Khan, from the 2011 campaign to commemorate her, to the biography, Spy Princess: The Life of Noor Inayat Khan by Shrabani Basu to the planned docu-drama, which at the time I had not yet watched.

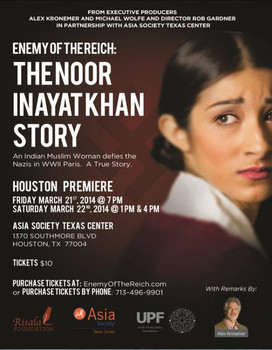

I have since watched the one-hour film, which is available to stream here. Enemy of the Reich tells the story of Noor Inayat Khan, “a young Muslim woman who sacrificed her life to fight against Nazi domination.” The film is produced and directed by Rob Gardner, whose credits include Arab and Jew: Wounded Spirits in a Promised Land, Inside Islam: What a Billion Muslims Really Think and Cities of Light: The Rise and Fall of Islamic Spain.

The documentary opens in media res, with Khan joining Winston Churchill’s Special Operations Executive (SOE). We are then taken back to the beginning of the story, following the cryptographer Leo Marks as he looks into Khan’s background to find out why she is struggling with the coding aspect of her training as a wireless operator. Through this set-up, and returning at various points to Marks’ perspective, we are introduced to Khan’s family history, and swept into the tale of how Hazrat Inayat Khan, a spiritual teacher from India, travelled to America and met and then, after a couple of complications, married Ora Ray Baker, and how the family came to live in Paris. The story then returns and picks up the rest of Khan’s story as she completes her training, becomes a covert agent, and returns to Paris as a wireless operator.

From the beginning, Khan’s religion is part of her background, in terms of how this aspect was seen by others in the SOE – in the sense that it is not her Muslimness that is particularly strange, but the idea of this slight, determined, idealistic, half-Indian, half-American woman who was raised in a Sufi home in Paris, and who had written a book of fables for children. As historian Dr Thomas Childers says, “there was something that seemed almost otherworldly about her, which struck them as exotic…given her name and her background.”

In my previous post, I mentioned that, in reading some of the reviews and articles about Khan, I was struck by a repeating reference to her and her father’s Sufism. Again and again, in these reviews, we are informed that Khan was “raised in the pacifistic Sufi Islamic tradition in France.” Or that she was “brought up in the mystical Sufi tradition” and therefore “abhored violence.” I’ve always been struck by the eagerness with which some people latch onto to the “Sufi” label as the identifier of the good, the cuddly, the mystical, the easy-going “Good Muslim.”

In the documentary, however, this focus is connected to the unique upbringing Khan had growing up in the house that her father named Fazal Manzil, the House of Blessings, with the comings and goings of an international crowd of Sufi devotees, rather than from any fuzzy idea of the innate goodness (and only ever goodness) of the “Sufi message.” Instead, we get religion scholar Dr Homayra Ziad’s pithy no-nonsense summary: “Sufis are Muslims, first and foremost, and Sufis can be Sunni, they can be Shia, they can be from any theological or any school of law.”

The more mystical language is left to one of Khan’s nephews, Pir Zia Khan, who is president of the Sufi Order international. At various points, Pir Zia explains concepts such as “lah illah ila allah” beyond the translation “there is no god but God,” giving it a more universalist mysticism: “there is nothing at all except the divine reality.”

Pir Zia speaks of Noor’s “deep commitment to core spiritual values that were unshakeable” and out of all the speakers, he is the one who most insistently attributes her actions to “a level of faith, of resilience, trust in the divine beneficence…only that faith could have carried her through.” Pir Zia mentions that the House of Blessings was about life devoted to living by what is preached, by service to the poor for example. Another nephew, David Harper, notes that the devotees of were probably upper class. Both nephews, however, recall that Inayat and Ora’s children always tried to live by what they had been brought up to hold dear – whether this was “core spiritual values” or “good character” is only a matter of language.

The acting is more or less what you’d expect of a docu-drama, except for one point in the film, where the focus on Khan’s uncommon idealism, in particular her inability to lie, is taken to a point that strains credibility. In the scene where Leo Marks finally succeeds in cracking the code of this “otherworldly” woman, and we are told, with an air of revelation: “she seemed otherworldly because she was from another world.” Marks’ epiphany about Khan’s otherwordly idealism makes sense as the culmination of his research into her upbringing; it makes less sense if we are also expected to believe that Khan was a woman of determined character.

At the very beginning of the documentary, there is a long list thanking various family members, and the narrator clearly had a difficult time with the pronunciation of the names – there is a strong, palpable sense of relief when we get to “the Pioneers Club of Unity Foundation.” Perhaps because of the mangled pronunciations at the beginning, I was filled with misgiving about the exoticization to come. However, this proved unfounded. Enemy of the Reich embeds Khan’s story in the historical context, without making too much of her faith. One example of the many little things that I was pleasantly surprised by was that the hour long documentary was almost devoid of the stereotypical “Eastern” music that typically inundates anything to do with any country that lies in the geographical range between Morocco and India – except for a few strains here and there, such as when her father is introduced with the words “he was a Muslim, born in India.” Most of the time though, the music and the wonderful narration by Helen Mirren sweeps you into the story of this extraordinary woman, who was a writer of fables, an Allied SOE agent, and as it happened (only as it happened), Muslim.