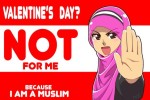

I want to take a temporary (temporary, I promise!) break from our moratorium on headscarves to highlight this article, which actually deals with many of the points I brought up in a post a while ago, asking why people get so caught up in headscarves and burqas when there are so many bigger fish to fry.

Faisal al Yafai, a London-based journalist, writes on the Guardian’s Comment is free about the need for Western feminists to get over the veil, and speculates on some of the reasons for the obsession with the veil. Particularly well-put was his point that:

There’s no doubt the veil is used by some as a way of marginalising, controlling and dominating women. It is used to relegate women to second-class citizens, to deny their sexuality and even to threaten sexual violence. But the veil, a piece of cloth, does not have the power to do that. Only societies do. Focusing on the former does not reform the latter.”

As he says, the scarf does get imposed in some situations, in a way that is oppressive to the women forced to wear it. But if we focus only on the scarf, we’re missing the bigger picture of oppression within that society. Eliminating the veil alone is never going to magically bring about liberation for all women.

One reason that al Yafai proposes for the obsession with the veil among western feminists is the “lack of an overarching narrative” in feminism, in contrast to earlier periods where women rallied around struggles for the right to vote or for abortion rights. This, he argues, leads to confusion as to where feminists should channel their energy, and prompts some to channel their energy towards less significant but more tangible issues, rather than confronting more nebulous challenges such as “societal expectations.” This was an interesting point that didn’t come up in our earlier discussion on MMW about why the scarf gets talked about to the extent that it does.

On one hand, it makes sense, because the veil is certainly something visible and material, perhaps easier to identify and quantify than other forms of oppression. On the other hand, I think there’s more at play than simply a lack of a bigger picture. Part of this may be a resistance to admit that the victories of women’s movements in the west, although significant, remain incomplete; many of today’s feminists often seem to prefer to identify oppression elsewhere, rather than to admit that their own society still constrains them in so many ways. The headscarf ends up fitting well into this framework, since it is seen largely as affecting “other” women in “other” places, leaving western women to continue to see themselves as emancipated. Mainstream feminist movements also have a history of not being very good at dealing with interlocking forms of oppression; economic injustice and war are rarely positioned as “women’s issues” within mainstream discourses, while the veil certainly passes the test of being something affecting women specifically.

(Of course, I’m totally generalising here, as does al Yafai in his article, about feminists in the west. Lots of western feminists are way smarter than this. In fact, to a large degree, this discussion applies not so much to feminists as much as it applies to those who co-opt supposedly feminist principles when trying to justify wars and other interventions in Muslim societies.)

Rawi made a great comment when I first posted about the overemphasis on the veil, arguing that people often end up conflating the sign with what is signified by it, and then coming to understand the clothing as the oppression, rather than as one manifestation of a society intent on controlling and policing women in various arenas. (Note that this discussion was focused on situations where clothing was imposed, and does not imply that headscarves should ever be uncritically understood to signify that their wearers are oppressed.) The problem isn’t necessarily that the veil gets talked about, but that the discussion so often stops there, and assumes that the fabric on a woman’s head is so oppressive that we need not go beyond it and ask other questions about what her own biggest concerns are.

As always, comment guidelines apply. We’re talking about how this clothing is seen and discussed, not about whether it’s obligatory for Muslims, and not about whether it is oppressive.