This originally appeared on the blog epiphanies, written by Tasnim.

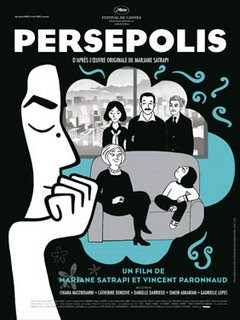

Persepolis, the animated film based on Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel, will be released in the US on 25 December. The film, like the novel, is in black and white and just as visually striking. Satrapi says that she sees “images as a way of writing” in a more accessible, international language: “when you draw a situation—someone is scared or angry or happy— it means the same thing in all cultures”.

Satrapi refused several offers to buy the rights for ‘adaptations’, being aware that ”normally when you make a movie out of a book, it’s never a success.’’ But whether or not Persepolis the film gets it right, it does seems unrealistic to ask a 90 minute film to pack in all the qualities Gloria Steinem praised Satrapi’s book for having – “the intimacy of a memoir, the irresistibility of a comic book, and the political depth of a the conflict between fundamentalism and democracy.”

Such neatly phrased praise decorates the blurbs of bestselling books everywhere, and is possibly not intended to be taken as strict truth stripped of all rhetoric. But it seems to overlay a genuine feeling that reading the personal experiences of an oriental is conducive to comprehending “a world, most Westerners can scarcely comprehend”.

That quote comes from the Washington Post Book World, referring to Mernissi’s memoir, Dreams of Trespass, which is given its own triple set of helpful qualities: “its good humor is unwavering, it tempers judgmentalism with understanding, and it provides a vivid portrait…” of that other, alien world. That is, Mernissi’s memoir is intimate, irresistible and, also, as enriching its entertaining exotic aspect, it provides ‘political depth’, in the same way that waging war has the benefit of geography lessons.

It seems to me that having the political depth of the conflict between fundamentalism and democracy requires a lot of ‘depth’. Such depth as might perhaps extend beyond the personal frame of a memoir and into history. These are conflicts that Satrapi’s dry remarks acknowledge. As she says, “if I pretend that I was sitting in a house worrying day and night about my country, that would be a big lie.”

Memoirs don’t seem the most ideal form for books which attempts to explain a whole other world to western eyes. Being a memoir, its world-explicating power is rendered somewhat suspect by the fact that it is contained within such a subjective frame. Perhaps like the use of images – which, Hamid Naficy points out “provide kind of a visual supplement to the words that makes it easier for people — foreigners and whatnot — to imagine what she’s talking about,” memoirs make political depth easier to digest. The personal/political memoir leaves writers in a double bind though. On the one hand, Satrapi says “I have to defend my country because the world is not going well… I would have wished that I couldn’t sell any books because everybody already knew about it.” On the other hand, she depends on the world not “going well” to sell, her fame boosted by blurbs that recommend her as an aid to understanding an incomprehensible world. It’s a difficult balance. Satrapi does her best to get beyond the two dimensional view, saying that what is incomprehensible is not ‘her’ world, but the very idea of splitting the world into worlds. As she says: [Bush] calls us the Axis of Evil. If it was that easy then let’s exterminate the bad ones and let the good ones live happily.

Her cartoons might be in black and white, but her views aren’t, and in this her works differ from what Fatemeh Keshavarz calls the “New Orientalist” narrative, referring to novels by writers like Azar Nafisi, Khaled Husseini and Asne Seierstad, as fitting the pattern of the narrative that: “reduces the contemporary Muslim Middle East to an uncomplicated black and white world of villains (usually Muslims) and victims (usually sympathizers with the west). A vast number of people and events, that don’t fit either category, are simply left out of the picture.” Satrapi, on the other hand, is keen to point out that her books show that “The world is complex. Even in my book I show a mullah who is good.”

Despite that ‘even’, whether it’s the shifting definition of evil (“At one time the evil was the Soviet Union then Ayatollah Khomeini then Saddam Hussein then Osama Bin Laden then Saddam Hussein again. It could be UFOs from another planet”) or the belief that Iran is Arabia (“There are no camels in my country because it’s cold in Tehran in the wintertime”) Satrapi, like Mernissi, attacks the cartoon image of the Middle East. She condemns the fact that “”If something bad happens in the East, it is immediately related back to religion” words which parallel Keshavarz’s terms, the “Islamization of wickedness” and the “westernization of goodness”. These parallel trends are central to books like Azar Nafisi’s ‘New Orientalist’ Reading Lolita in Tehran, of which Keshavarz says: “there is a convenient generic shape shifting involved that allows the author to move between the freedom of writing a personal memoir and the authority of providing an eye-witness factual report.”

Satrapi’s might not be ‘reporting’ but she does do some ‘explaining’. Which can mean changing people’s perception of Iran by reminding them that once upon a time there was an Iran which had never heard of Islam. And it necessitates taking up the infamous “the politics, not the people” shield. Satrapi insists ”I like American people very much—really, there is some kind of enthusiastic, candid way of being American that I really, really love—but the American government is just shit.”

Satrapi’s might not be ‘reporting’ but she does do some ‘explaining’. Which can mean changing people’s perception of Iran by reminding them that once upon a time there was an Iran which had never heard of Islam. And it necessitates taking up the infamous “the politics, not the people” shield. Satrapi insists ”I like American people very much—really, there is some kind of enthusiastic, candid way of being American that I really, really love—but the American government is just shit.”

But in breaking down the idea of Iran as a different world, she at times has to construct another world in which to put those unsightly incomprehensible phenomena which don’t appeal to western sensibilities. Maintaining that “As an Iranian, I feel much closer to an American who thinks like me than to the bearded guy of my country,” might seem a profound politically deep comment on fundamentalism and democracy to some, but then it also sounds perilously close to what a Native Informer might say, as Hamid Dabashi calls writers like Azar Nafisi – writers who put their work “at the service of US ideological psy-op.” Satrapi’s words are clearly intended to express a personal view – but she prefaces them with ‘as an Iranian’. Her perhaps throwaway comment seems a perfect analogy to reactions to her memoirs which assume her position as an ‘insider’ makes her an authorative guide to an alien world.

The danger of that is that many of these memoir writers – these insiders – are in fact exiles, often outsiders. Hamid Naficy says that their memoir writing is in part a form of compensation: they “couldn’t go back, so they imagined what it was like in Iran.” Satrapi knows that exiled feeling: “I am a foreigner in Iran,” and yet, she can explain Iran to the West. She can speak for a world and render it comprehensible, even though she acknowledges she is a foreigner to that world, because she is after all ‘only’ writing her memoir.